Cemile Çağırga: A Girl is Freezing Under State Fire

“As a child born in the southeast, after the ‘90s, you’re not really a kid. During your infancy, you’re really a child between 1-5 years old. As a 6-year old, you’ve actually grown up and are considered to be 15 years old. When you turn 10, you’re actually 20. After 15, you feel like you’re 40 years old.”

İmren Demirbaş, 16-year old Kurdish girl, Diyarbakir [1]

“Look here, here, underneath this black marble

A child is buried; if he had lived for one more recess

He would have risen from nature to the blackboard.

He was killed in a lesson of the state.”

Ece Ayhan

“The photograph is like a quotation, or a maxim or proverb,” writes Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others. A short while ago, the world quoted one of its most devastating stories through a photo taken on the shores of Turkey. The Mediterranean opened like Pandora’s box and washed up a little Kurdish child from Kobanî in Syria, Alan Kurdî, to our feet in his best clothes. Despite our ethical efforts to avoid looking at (and thus, consuming) this picture, and those to resist sharing it on social media, we all have been exposed to it in one way or the other. Alan’s tiny little dead body will keep lying on the edge of the waves in our minds… We are all shaken and terrified by his image.

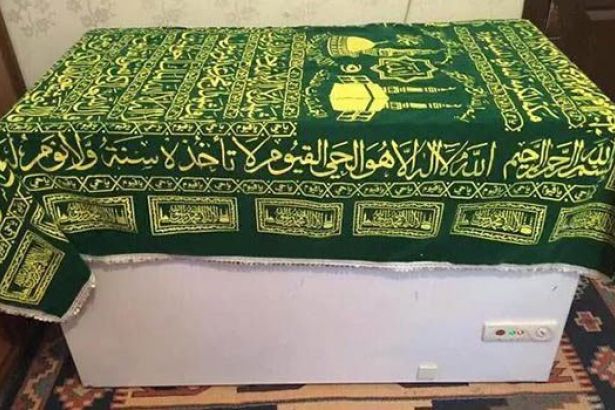

Now I invite you to look at another photograph, hoping that Alan’s picture has taught, at least some of us, to look beyond the instant shock of an image. This photograph does not reveal itself as an image of immediate dread and terror. It rather terrifies you gradually with what it conceals. This is an image of a refrigerator sitting in the middle of a room in a house in the Kurdish town of Cizre—a town that stayed under military curfew for nine days and was heavily attacked by the Turkish state security forces. The refrigerator in this image, covered with that green cloth of the Qur’anic script, is transformed into a coffin to preserve the dead body of a ten-year old girl, Cemile Çağırga, another Kurdish child.

The body of Cemile Çağırga in a deep freezer. Image courtesy of Sol.

Cemile was shot to death by the state while playing with her friends in front of her house. After being denied a proper burial, her family could do nothing, but put her body in a deep freezer to prevent from rotting. Due to the state-declared curfew, their everyday life shrank into their home space with no permission to enter or exit. In fact, the word curfew comes short of describing what happened in Cizre. Locals from Cizre testified that their town was under siege. 23 civilians were killed and 7 of them were children. Random heavy attacks severely injured and killed some people in their apartments, as they waited for this inferno to come to an end. The prolongation of the waiting time itself induced a serious humanitarian crisis, including shortages of food, power and water, as well as the denial of basic emergency health care. A 35-day-old baby died due to state-banned ambulance services in the streets. Wounded people were left alone with their self-healing practices within the confines of their houses. Some accounts on social media claim that even the call for prayer was suspended in town and snipers replaced imams in the minarets of the mosques.

Under these exceptional conditions, it is not surprising to discover that not only the ordinary life, but also the ordinary death (i.e. its customs, burial practices, funeral rituals, relations and symbols of mourning, etc.) was suspended. The words of Cemile’s mother carry all the weight of death under siege:

She died in my arms. That night, I took my daughter’s body to my bed and slept her on my chest. In the morning, I applied henna on her hair and hands. Then we washed her body and wrapped her in shroud (kefen). Just to stop her corpse from rotting, we put my daughter in a deep-freezer that we brought from my brother-in-law’s. Her body waited in the freezer for three days. Then the deputies came and took her body to the hospital morgue.

The second image below is of Cemile’s funeral ceremony. As the family and the community are taking her body to the burial site on their shoulders, the women of her family hold white flags and try to tell the police not to shoot, that they are not a threat.

Women waving white flags leading a funeral procession in Cizre. Images courtesy of @senolakdag and @EndezyareKurd

These images went viral on social media, causing significant trouble and disturbance among the supporters of peace. However, for some others, they failed to depict and testify the “reality” of the atrocity and cruelty put into play under a nine-day long state occupation. The refrigerator image in particular was subject to ignorance, negligence or complete denial. In addition to belying the image, some people’s imaginative faculties led them to go a step further and locate the image in another place under occupation at the hands of another vicious state: Some claimed this photo was taken in Gaza under Israeli occupation, not in Cizre. Nevertheless, the evil was too proximate, too intimate, too close to come to terms with, and hence, many Turkish people did not want to see it. They themselves turned evil in this denial.

This distortion shows us one important thing: the story of siege and colonization, besides being about a story of material conditions and relations of life, is also a story that is strictly tied to the symbolic domain through its production, distribution and consumption. This particular form of control and oppression makes it possible to export a record of violence or a register of history to another colonial landscape. This self-denying logic makes this image alien to oneself and rewrites it as a proof for others’ stories of occupation. In so doing, it denies, fails, shifts, alters, erases, and most importantly, colonizes a symbol that stands for a significant visual record of history. It is yet another story of looting of a record within a geography that has been marked by similar histories of violence, including the Armenian Genocide in 1915, the Dersim Massacre in 1938, the Istanbul Pogrom in 1955, the coup d’état in 1980, and the Diyarbakir Prison in 1981-84. In fact, it is within this particular tradition and legacy of state violence that one can understand the killing of Cemile and of other children in Cizre, a particular manifestation of state violence that aims to annihilate when it cannot assimilate.

A brief death record of Kurdish children

Cemile is not the first killed by the Turkish state security forces. Nor will she be unfortunately the last. The state security regime killed 576 children between 1988-2014. The referred record ends with Berkin Elvan’s death, a 15-year old boy who was severely injured with a gas canister shot at his head by the police when he was on his way to the grocery store in his neighborhood during the Gezi protests. He died after staying in coma for nearly nine months.

Kurdish children had to face the most severe forms of state-led atrocities especially throughout the ‘90s—an era marked by the Turkish state’s brutal use of violence against PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) guerilla members, the Kurdish people who resisted the assimilation policies of the state and the members and/or sympathizers of other Kurdish organizations. Displacement, evacuation, demolition, kidnapping, disappearance, rape and torture blockaded everyday life in Kurdish landscapes, inscribing its terror and traces on the bodies and memories of many generations, including those of children. The state killed a total number of 373 Kurdish children in this period, reaching its highest death toll in 1992 with a number of 117 children that year alone. [2]

When it comes to 2000s, Uğur Kaymaz’s and Ceylan Önkol’s murders marked this decade. Uğur Kaymaz was only twelve when the police shot him to death by using “proportional force,” as was declared at the court defense of the police officers. The Forensic Medicine removed thirteen bullets from his 12-year old body. Those thirteen bullets that were justified as a “legitimate defense of the policemen” in their encounter with a “terrorist.” Ceylan, a 12-year-old Kurdish girl, on the other hand, was killed in a mortar blast in 2009, while herding her sheep in her village. Her mother had to collect in her skirt the shattered pieces of her daughter’s body spread over a 150 meter-radius.

2006 is another remarkable year in the death records of the state. In March 2006, Kurdish people wanted to organize a public funeral ceremony in Diyarbakir for six guerillas from HPG (People’s Defense Forces—the armed wing of the PKK), whose burned bodies testified their cause of death to be chemical weapons. Upon their return from the burial, the police harshly attacked the funeral crowd with pepper gas, water canons and armored vehicles. The clashes between the police and the people escalated and spread over to other Kurdish cities, starting a wave of serhildan, a public Kurdish rebellion against state oppression. Children took part in these protests as political actors, throwing stones at the police and resisting against them. During this upheaval, 23 children were killed. In the course of this specific targeting of children, the state police and security forces not only killed many, but also subjected many more to torture and imprisonment.

Of course, another hard-hitting day on the state calendar of massacres was the Roboski Massacre on December 28, 2011. On this day, a Turkish drone-strike killed 34 Kurdish civilians, 22 of whom were under 18 from Roboski, a village on the Turkish side of the Turkish-Iraqi border near Syria. These children, who provided for their families by smuggling cigarettes and diesel fuel from across the border, were allegedly mistaken for terrorists and killed in what was labeled “an operational accident”.

And now Cizre… As I wrote this piece, the death toll for children was seven. The state extended the curfew to other towns, including Yüksekova and Diyarbakır, the largest city in Turkey’s Kurdistan.

This brief history demonstrates that neither injuries nor deaths of Kurdish children are incidental to their families and communities. Rather, it attests to the fact that they are products of a systemic targeting of lives and deaths of those who are rendered disposable, consumable, and thus, erasable from the surface of this landscape, as Nick Glastonbury has recently argued in Jadaliyya.

Killing the symbolic, the intimate, and the sacred

War displaces, evacuates, shatters and breaks apart physical and emotional worlds. But it also corrupts one’s sense of time, map of meanings, world of symbols and domain of the intimate and sacred.

In her piece on Ekin Wan, a PKK guerilla woman whose dead and tortured body was exhibited naked by the Turkish soldiers on the streets of Kurdistan, Nazan Üstündağ draws our attention to the sovereign’s warfare over the dead of the oppressed. Using the death of the other, states attempt to punish communities beyond mortality, and inscribe themselves on communal relations of intimacy. She continues to argue that states ruin and poison the relations with the dead, and for that matter, they reshape the relations with the hereafter, with the divine and with the world of faith.

Now, once more, I ask you to look at Cemile’s picture very closely! Here in this image, another Pandora’s box is staring directly at us, whether it remains closed or is opened, reveals the petrifying face of state terror in one of its most naked and intimate sovereign forms. This is a terror that lays siege to the social, political and intimate life of death by striving to ruin the flesh of the community in the mirror image of Cemile. At times of war, death is not a threshold, not an end but it may easily serve as a continuation of an existing terror or as a beginning of a new one. In his piece on the politics of death, Hişyar Özsoy notes that a merely biological killing is not enough for nation-states when it comes to those who rebel against their commands. The nation-state, as the sovereign, resorts to every possible means to prevent the bodies of those dead from gaining a significant meaning and a substantial value. This way, as Özsoy continues to argue, the sovereign further kills the people on the symbolic, as well as the political register, and endeavors to separate the dead from the life of a community. Hence, when states occupy not only the domain of life, but also that of death, it is a rip-apart in the intimate life of the community. In ‘90s, the state in Turkey used this dirty play with the dead as a widespread war strategy by disappearing Kurdish people, dumping the dead guerilla bodies in garbage and preventing the community from practicing their burial and funeral rituals.

Political life and social theory have taught us that the sovereign is the one who decides over life and death. Who should live; who should die; in what way; and what values and meanings life and death can gain are at the heart of the sovereign efforts to draw, organize and regulate the boundary between life and death. That said, answers to these questions also inform us about people’s stories of resilience, struggle, and resistance. Nevertheless, there are always multiple fine lines between which stories are heard and which ones remain unheard, or which stories become (hyper)visible and which ones stay invisible.

For this reason, one last time, I want to draw your attention to the visual component of these relations with the sovereign(s). Even when an invisible deed of injustice, act of violence or instance of suffering is rendered visible, there is no guarantee that we see it the same way. What “we” see and what “we” ignore or deny seeing is also a story of our particular relation to the sovereign, as well as our specific location in a transnational world of sovereigns that in tandem and globally produce and organize unequal chances of life and death. The visibility of children’s death and the circulation of images of their dead bodies at the hands of states and borders speak to these dynamics, and we should approach both Alan’s and Cemile’s pictures from this vantage point.

Alan’s image stands for a fierce reminder of how life and death is unevenly distributed, how our rights to mobility, nation-states and even home are unequally recognized (or denied altogether) in a transnational world. So does Cemile’s picture! It is up to us to be able to see Alan Kurdî’s now hypervisible washed-up body and Cemile Çağırga’s invisible frozen body together meeting in the same point: namely, the location of death, which is locally, nationally and globally produced on a daily basis by a set of sovereign actors, security regimes and war economies. And we are all implicated in their stories.

Acknowledgments: I want to thank Seçil Dağtaş, Dilan Okçuoğlu, Mai Taha and Çağrı Yoltar for their comments on an earlier version of this piece.

[1] İmren Demirbaş is one of the children in Little Black Fish (Küçük Kara Balıklar) (2014), a documentary on being a Kurdish child in Turkey. It is directed by Ahmet Haluk Ünal and Ezel Akay and available online with English subtitles at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hvYmmQc0ho

[2] These numbers are taken from the documentary, Little Black Fish.

![[The body of Cemile Çagirga in a deep freezer. Image courtesy of Sol]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/dondurucucopy3.jpg)